Leveraging Mid-Quarter Student Feedback to Improve your Teaching

April 2025

What?

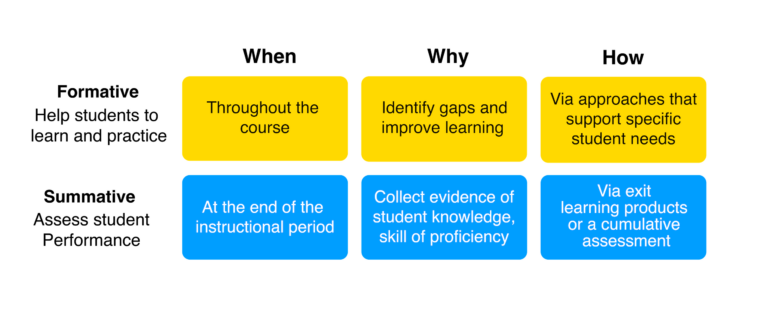

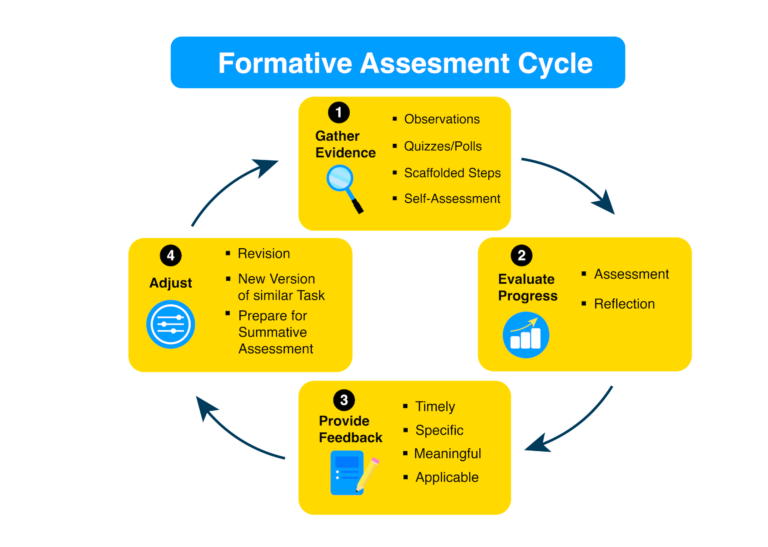

Students can provide valuable feedback on their course experiences. Student Experiences of Teaching (SET) surveys are administered at the end of each academic term. SET surveys are considered summative assessments, focusing on overall student outcomes in your course. While useful in informing the improvement of future offerings of the same course, these data do not allow for opportunities to make real-time changes to your current course. Formative assessments consist of information gathered from students by instructors throughout the learning process (e.g., mid-quarter). This feedback can then be used to make real-time changes to teaching practices and allow for course adjustments as needed (Black & William, 1998).

While there are several different ways to collect formative feedback, this guide will provide an overview of mid-quarter student feedback that is specifically designed to provide instructors with information about “what is and what is not working while time still remains for adjustments” (Payette & Brown, 2018: 1).

Using mid-quarter evaluations is also an opportunity to practice reflective teaching, which occurs when we critically evaluate our teaching by examining the assumptions that influence our practice. Brookfield (2017) explains that many of these assumptions come from our experiences as learners, conversations with colleagues, and academic research. While such sources can yield helpful information, they may not be useful in all situations or relevant to the student population. Reflective teaching allows instructors to intentionally examine their teaching practices, leading to continuous improvement and deeper student engagement.

Formative and Summative Assessment

Why?

Formative feedback can enhance the quality of instruction by providing instructors with insights into student engagement and learning. An instructor may use this information to adjust teaching methods in ways that can immediately improve student engagement in the learning process and foster a deeper understanding of course content (Morris et al., 2021). By providing ongoing insights, this feedback helps to create a collaborative and supportive educational environment for students. The following section outlines some key benefits of formative feedback.

Enhances Teaching Effectiveness

Formative feedback allows for real-time insights into student learning (Messier, 2022). It enables instructors to modify their teaching strategies to better meet the needs of their students, supporting ongoing reflective practice and an iterative teaching improvement process. Mid-quarter feedback can provide the formative data needed to identify learning gaps and provide more targeted instruction to facilitate learning for all students.

Creates a More Positive Classroom Environment

Mid-quarter student feedback, in particular, fosters an inclusive learning environment by encouraging open and authentic communication with all students. An important step in this process is to make an extra effort to not only collect and review student feedback, but also to let students know what you learned and how you will make changes to your course based on their feedback. This can show students that their feedback is important (Black, 2009) and help build trust between students and instructors. Moreover, engaging students in formative feedback actively brings them into the learning process, strengthening collaborative relationships (Sozer, Zeybekoglu, & Kaya, 2019).

Develops Essential Student Skills

When students provide formative feedback, they have the opportunity to reflect on their learning and their role in the learning process. Mid-quarter feedback also gives students agency to modify their learning strategies, helping them develop critical self-assessment skills, such as perception, metacognition, and self-regulation (Messier, 2022; Silva, Saiz, & Ossa, 2022). Additionally, it provides them with opportunities to practice skills — such as communication and collaboration with instructors — that are valuable beyond the classroom.

Increases likelihood of completing post-course evaluations

When students have the opportunity to provide feedback during the quarter, it demonstrates an authentic impact of their voice in the course evaluation process. As a result, students will be more likely to provide thoughtful responses and complete SET surveys at the end of the quarter (Young, Joines, Standish, & Gallagher, 2018).

How?

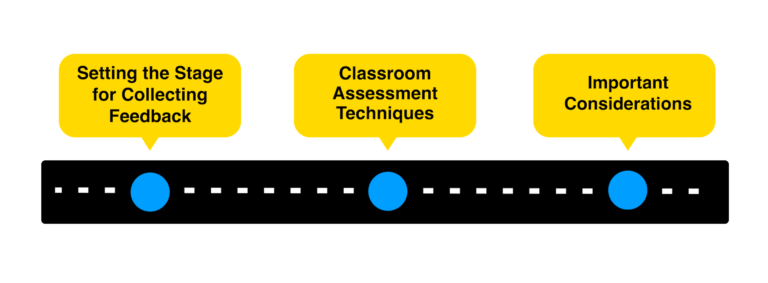

To effectively leverage student feedback, it is important to understand how to collect it in a way that will yield meaningful insights. This section explores strategies for collecting feedback, including important considerations such as setting the stage for gathering feedback, timing the collection of feedback, and course logistics such as class modality and size. Additionally, various assessment techniques will be discussed to help instructors identify feedback collection strategies that suit their unique classroom contexts. The section will end with recommendations for sharing feedback with students.

Roadmap to Leveraging Student Feedback

Setting the Stage for Collecting Feedback

Effective feedback begins with a clear purpose. For example, are you trying something new in your course? Did students struggle with an activity or section of an exam? Do you want to make sure students comprehend the material? In other words, you should establish why you are collecting midterm feedback and how it will be used, and most importantly, communicate these expectations to your students.

Happel and colleagues (2024) identified five specific aspects of teaching that can be targeted using mid-quarter evaluations: (1) course structure and clarity; (2) student engagement and participation; (3) course assignments and usefulness of feedback on those assignments; (4) instructor communication; and (5) learning environment. The questions on a mid-quarter evaluation can then be tailored to the type of information you are seeking. They might be specific to particular assignments or lessons, or broader to get feedback on students’ understanding of course learning objectives.

Students are more likely to provide constructive feedback if they understand that their efforts will contribute directly to course improvements (Happel, et al., 2024). Additionally, framing the mid-quarter evaluation as a tool for improvement can encourage honest responses and increase engagement (Donlan & Byrne, 2020).

In addition to establishing your purpose, it is important to take into account various timing considerations. First, when will you collect your feedback? Collecting feedback too early in a quarter may not give students enough time to experience relevant factors in your course. Waiting too late in the quarter may not provide enough time to respond to student feedback and implement meaningful course adjustments. Therefore, consider implementing a survey during weeks 4 – 7 of a 10-week quarter, depending on the major milestones of your course. Second, how much time will you need to review and respond to feedback? Keep in mind that even minor changes, such as clarifying expectations, can improve student perceptions of the course (Sozer, Zeybekoglu, & Kaya, 2019), particularly when students feel that changes are in response to their feedback.

Classroom Assessment Techniques

There are a variety of methods one can use to collect feedback from students, and this section will provide an overview, including the benefits of two strategies, surveys and exit tickets (for a review of additional methods, see Angelo & Cross 2012 or Payette & Brown 2018).

Surveys

Surveys are among the most widely used techniques for gathering mid-quarter feedback, as they can be used in-person and online, can be collected anonymously, and are appropriate for courses of any size. Short, structured surveys can include a mix of multiple choice, rating scale, and free response questions. Survey questions can be general (e.g., On a scale of 1-5, with 1 being the least helpful and 5 being the most helpful, indicate the extent to which you find the instructor’s explanations helpful), or they can address specific aspects of the course, such as difficulty level or course pacing compared to other courses (Payette & Brown 2018). Midterm surveys can also ask students to reflect on their levels of engagement in the course and with the instructor.

Surveys are particularly effective in large lecture courses, particularly given the variety of methods to capture data. For example, they can be integrated into Bruin Learn or can be distributed via Google forms (use these guides to learn how to add a survey to your course website and view the results; note that all options in Bruin Learn do allow instructors to identify students and their responses). Quantitative data allows for quick comparisons of student experiences, while qualitative data can allow for deeper insights. Often, a mix of quantitative and qualitative survey questions works well to capture student sentiment and allows students to reflect on their learning. However, keep in mind when drafting survey questions how much time you want students to spend completing the feedback form and also how much time you will have to review it.

Exit Tickets

While a mid-quarter survey can be administered in class or outside of class, an exit ticket provides the opportunity to collect brief responses during class, typically at the end of a lesson or lecture (Angelo & Cross, 2012). Exit tickets can provide quick feedback with immediate insights about student learning on a topic, and do so by asking a single question and requesting a short response. A benefit of using exit tickets is the ability to combine a low-stakes assessment of student learning with feedback on teaching and course design. They can be collected using polling platforms, such as iClicker, and provide quick insights with high response rates (Koo, 2024). See this helpful guide from the TLC for more information about polling.

Exit tickets are referred to by a variety of names, each of which tends to focus on different types of questions. Suggestions for mid-quarter exit ticket questions are as follows:

- Minute Paper: What was the most important thing you learned today?

- Muddiest Point: What is still unclear from today’s class?

- One-Sentence Summary: Summarize the lecture in one concise sentence.

- Reflection on course activities: What activity was most supportive of your learning and why? What aspects did not seem to support your learning?

- Reflection on learning: What could you have done differently before class to help you learn better?

- Application: How can you apply what you learned today to [insert learning outcome/skill]?

Important Considerations

Mid-quarter feedback allows instructors to make timely course adjustments to improve their students’ learning experiences. The technique one uses should be aligned with course modality (online versus in-person) and class size.

Course modality shapes the student experience, including participation and engagement, thus can influence the effectiveness of feedback. For example, the lack of in-person interaction in online courses may make it more difficult to gauge student sentiment. It may help to add engagement-specific questions in this context. On the other hand, students may be hesitant to give honest, critical feedback while in person. In both cases, providing students with the opportunity to share their thoughts anonymously can create the opportunity for them to provide more candid feedback.

It is also important to take into account course size when preparing a mid-quarter evaluation. It may be harder to go through qualitative data (e.g., responses to open-ended survey questions or exit tickets) in a course with high enrollment. On the other hand, students may be more hesitant to share feedback in a small course. Even if responses are collected anonymously, they may feel they are identifiable. To mitigate this concern, it helps to remind students that you will not be connecting their responses to any identifying information.

Understanding and Sharing Feedback

Once mid-quarter feedback has been collected, instructors should organize the data, identifying trends and then communicate findings to students, summarizing their responses and addressing potential concerns (Payette & Brown, 2018). This process allows instructors to pinpoint actionable insights without being overwhelmed with information. Ideally, you should communicate your responses to students within one week to make sure there is enough time in the quarter to implement the proposed changes (Donlan & Byrne, 2020). This can be done during class by providing a quick overview of what you learned from the student feedback, an announcement on Bruin Learn, or a recorded video.

Organize and Identify Trends

First, data needs to be organized. Quantitative data (rating scale and multiple choice questions) can be summarized using average scores and distribution patterns (i.e., the range of the responses you receive) to identify trends. Qualitative data can be summarized using thematic analysis, which can be done by grouping comments into categories, such as areas for improvement, strengths of the course, or confusing concepts. For example, Angelo and Cross (2012) recommend organizing responses using the “Start, Stop, Continue” method. Here, feedback is organized into three categories, as follows:

(1) Start: what should the instructor begin doing?

(2) Stop: what isn’t working well?

(3) Continue: what is working well and should remain unchanged?

When organizing the data, instructors should focus on trends that appear across multiple student responses rather than fixating on one or two that are inconsistent with the overall sentiment. Additionally, it is useful to address contradictory feedback. That is, how might you respond when a large number of students want more group work and another large subset requests more individual assignments?

Communicate Findings to Students

Students are more likely to positively engage with feedback in the future when they see that it leads to change (Miller, O’Connor, & Ford, 2024). Thus, transparency is essential to the feedback process. Instructors should share a summary of responses in class or on the course website, including an explanation of what will change and why. If relevant, findings should be shared with teaching assistants (TAs) both to model this type of reflective practice and ensure they are aware of and can be part of any changes that may result. Additionally, instructors should acknowledge limitations. For example, as described above, it is possible that students will provide contradictory requests. Moreover, some student requests may not be feasible or in service to your course goals.

Getting Started

- Keep it short and focused: students are more likely to complete shorter surveys (10 questions or fewer). If time allows, have students submit feedback during class.

- Use a mix of question types: if possible, combine multiple choice, rating scales, and open response questions for balanced insight.

- Clarify the purpose: let students know why you are asking for their feedback and how it will be used.

- Ensure confidentiality: assure students that responses are anonymous to encourage honest and constructive feedback.

Share findings with students: provide a summary of the feedback and explain how you will use it to make changes to the course.

Citing this Guide

UCLA Teaching and Learning Center (TLC). (2025). Leveraging mid-quarter student feedback to improve your teaching. Teaching and Learning Center at the University of California, Los Angeles. Retrieved [today’s date].

Additional Resources

“CEILS Teaching Guide: Based on Student Feedback”–A teaching guide with tips to help you gather and implement student feedback throughout the quarter.

“Mid-Quarter Surveys: Best Practices and Sample Questions”–a list of potential midquarter survey items includes more than 50 examples. This list of potential midquarter survey items includes over 50 examples, along with sample introductory text.

References

Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (2012). Classroom assessment techniques. Jossey Bass Wiley.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the Black Box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. London, UK: King’s College School of Education

Brookfield, S. D. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. John Wiley & Sons.

Brown, M. J. (2008). Student perceptions of teaching evaluations. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 35(2), 177-182.

Happel, C. C., Rohrbacher, C., Cooks, T., Korentsides, J., Keebler, J. R., Van Ommen, C., … & Barbeau, L. (2024). Validating the Critical Teaching Behaviors Midterm Feedback Instrument for enhanced teaching effectiveness and student engagement. To Improve the Academy (TIA), 43(2).

Diamond, M. R. (2004). The usefulness of structured mid-term feedback as a catalyst for change in higher education classes. Active Learning in Higher Education, 5(3), 217-231.

Donlan, A. E., & Byrne, V. L. (2020). Confirming the factor structure of a research-based mid-semester evaluation of college teaching. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 38(7), 866-881.

Messier, N. (2022). “Formative assessments.” Center for the Advancement of Teaching Excellence at the University of Illinois Chicago. Retrieved January 17, 2025, from https://teaching.uic.edu/resources/teaching-guides/assessment-grading-practices/formative-

Miller, E. E., O’Connor, S. K., & Ford, J. (2024). Small-Scale Changes with Big Benefits: Addressing Low Course Evaluation Scores in a Pharmacy Management Course. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 88(9).

Morris, R., Perry, T., & Wardle, L. (2021). Formative assessment and feedback for learning in higher education: A systematic review. Review of Education, 9(3), e3292.

Payette P. R., & Brown, M. K. (2018). Gathering mid-semester Feedback: Three variations to improve instruction. IDEA Paper #67.

Rivas, S. F., Saiz, C., & Ossa, C. (2022). Metacognitive strategies and development of critical thinking in higher education. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 913219.

Sozer, E. M., Zeybekoglu, Z., & Kaya, M. (2019). Using mid-semester course evaluation as a feedback tool for improving learning and teaching in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(7), 1003–1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1564810

Young, K., Joines, J., Standish, T., & Gallagher, V. (2018). Student evaluations of teaching: the impact of faculty procedures on response rates. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1467878