Leveraging Self-Reflection to Improve your Teaching

April 2025

What?

As an instructor, self-reflection is a tool you can use to think about your instructional practices, teaching habits and beliefs, and classroom policies to assess their effectiveness and strive to improve as an educator (Jakfar and Rahmatillah, 2023; Pedrosa-de-Jesus et al., 2017). John Dewey, an early proponent of reflective teaching and learning, said in an oft-quoted line: “We do not learn from experience. We learn from reflecting on experience” (Dewey, 1910/1933). Reflection is a critical component of learning for both you and your students. While you might carve out time during class for students to engage in reflective exercises, you may not prioritize dedicating time for thinking deeply about what you do, why you do it, and what you might do differently. Given the variety of work that goes into teaching, you might also struggle with deciding what aspect of your practice to reflect on; turning your observations into action; and assessing their impacts.

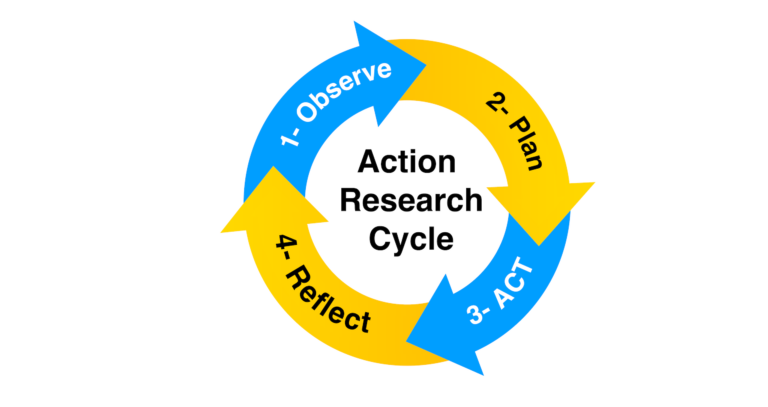

This guide provides an overview of a data-informed process you can use to engage in targeted reflection to implement iterative changes to your instruction. Within Scholarship of Teaching and Learning—interdisciplinary and practice-based research meant to advance improvements in teaching and learning—this four-step process is known as an action research cycle (Norton, 2019). To inform your action research cycle, it can be helpful to set a concrete teaching goal. Following a brief overview of the benefits of self-reflection, this guide provides suggestions for how to develop an effective goal; how to use the action research cycle to make observations on your current practice, as well as plan, enact, and assess changes to your practice in accordance with your goal; and, finally, how to incorporate habitual practices to make self-reflection an intrinsic component of lesson planning and other related teaching tasks.

Why?

Self-reflection has many benefits and is crucial to your professional development as an instructor. Self-reflection can lead to more engaged and effective teaching, which in turn can lead to improved student learning outcomes and academic achievement (Dweck, 2006; Brookfield, 2017). Taking time to think back over your interactions in the classroom can help you become more responsive and inclusive in your teaching practice, as you are better attuned to the diverse viewpoints, needs, and lived experiences of all your students (Juma, 2024).

Though developing reflective practices may take some time, it can save time in the long run by helping make instructional processes more efficient and providing an iterative approach to revision and even transformation of your classroom. For example, if you deliver a lecture that doesn’t go as expected, jotting down some notes about what you would change in your lesson plan immediately after class can make it easier for you to update your materials the next time you teach the course. Reflection also empowers you to make evidence-based or data-informed decisions about your teaching, with action planning based on feedback from students, assessment outcomes, and classroom observations (Juma, 2024).

Self-reflection can also help prepare you for higher-stakes evaluations of your teaching (such as putting together a teaching dossier for a promotion) by helping you clarify your teaching beliefs and values. Thinking about how and why you engage in particular pedagogical practices enables you to recognize your strengths and areas for growth, both of which can help you set appropriate teaching goals and inform efforts to improve the learning experience for students (Moon, 1999; Lubbe & Botha, 2020; Juma, 2024). This process can empower you to take ownership of your career trajectory, leading to an increased sense of agency, motivation, and job satisfaction (Locke & Latham, 1990; Fullan, 1991). Reflection can also benefit your general wellbeing by helping you cultivate self-awareness, so that you can remain mindful of your capacity, your needs, and your priorities, thus reducing the risk of burnout (Sutton & Wheatley, 2003). Using self-reflection to improve your teaching relies on a growth mindset and a commitment to lifelong learning: these are both values that, when passed onto students, empower them to set their own goals and take ownership of their learning process (Dweck, 2006). If you’re overseeing an instructional team, you can model a reflective practice and encourage TAs to develop their own, to support their professional development. For more guidance on mentoring and working with TAs, please see the Teaching with TAs resource developed by the TLC.

How?

This section introduces an action research cycle and explores how this tool can help you apply reflective teaching practices in targeted ways to make iterative and meaningful changes to your teaching and evaluate their effectiveness and impact.

Getting Started

Reflection might be carried out on your teaching content (whether your instructional materials adequately serve student learning or broader academic needs); your teaching practice (whether your instructional methods are aligned with research on how students learn); and your teaching premise (how you see your contribution to the overall institution or beyond the classroom) (Kirpalani, 2017). Start by considering what you would like to improve in your teaching, in other words, what are your teaching goals?

Developing Your Teaching Goal

Teaching goals should focus your priorities and resources (including your own time and capacity) on aspects of your instructional practice that are most important or meaningful to you. To help manage the scope of your efforts, consider developing teaching goals that are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound–that is, S.M.A.R.T. goals (O’Neill & Conzemius, 2009). To learn more about how to devise S.M.A.R.T. teaching goals, expand the accordions below.

Specific

To have a clear sense of purpose and direction with respect to your teaching goal(s), start by considering what you’re trying to accomplish and why. Think about where you will implement changes to your teaching (e.g., teaching strategies, learning activities, assessments). Then determine which obstacles you must clear or needs you must fulfill before setting out to achieve any particular goal.

Measurable

Consider how you will assess whether or not you’ve met your goal. What does success look like? What are some observable ways that you can determine whether your methods are successful? You can think about this as your data set.

Achievable

Ensure that your teaching goal is something you have the time, capacity, and resources to accomplish. Consider what training or support you may need to fulfill your goal. You may also need to adjust the scope.

Relevant

Reflect on the premise of your goal. Does it align with your teaching philosophy and values? Will it support your professional development and longer-term teaching goals? Making sure your goal feels relevant to you is crucial for staying motivated.

Time-Bound

Consider when you will implement changes. Are you revising aspects of a class you’re teaching in a future term, or are you making changes in response to the needs of your students in a current course? Either way, you must decide when you want to make a change, building in time to reflect on where you are beforehand and evaluate where you are afterwards.

Engage in Action Research

Once you’ve developed some teaching goals, you’ll need to engage in a process that enables you to achieve them. The action research approach is a cyclical and iterative method for improving your teaching (Norton, 2019). It involves four steps, which are as follows:

- Observe. Consider which aspect of your teaching you want to improve.

- Plan. Generate a course of action that involves changing something in your practice or content.

- Act. Carry out the change.

- Reflect. Notice the effects of your change and plan to start another cycle.

Observe

Consider which aspect of your teaching you want to improve based on student feedback, course data, and/or knowledge of research-based practices. Are you examining your teaching content, practices, or premise?

You might start by reviewing Student Experiences of Teaching (SET) surveys from previous quarters, or you might ask your current students for mid-quarter feedback by building a survey in Google Forms. For more about how to use SET surveys to inform your teaching, refer to this TLC Assessment Guide: Using Student Experiences of Teaching (SET) Surveys to Inform Teaching Practice. You can also reference this TLC Teaching Guide about gathering mid-quarter feedback: Leveraging Mid-Quarter Student Feedback to Improve Your Teaching.

The way you gather data about your teaching will look different depending on the modality and class size of your course. For example, in a large course or online lecture, you might use iClicker to quickly poll your class on their understanding of a particular concept. Asynchronous courses might benefit from Google Forms, so students can fill out their survey responses on their own time.

If you lecture in person and work with teaching assistants (TAs), you might ask them to help you circle the classroom as you all observe how students work through a particular problem set together. As instructional partners who observe you teach and have direct contact with students in smaller groups, TAs can also provide you with valuable feedback on how your teaching impacts students. You might also consider asking a colleague to observe your teaching and discuss areas of potential growth or improvement.

You might use tools like iClicker or Google Forms to gather data. Reference the Implementing Peer Instruction Using Polling Tools guide developed by the Center for Education Innovation & Learning in the Sciences (CEILS), with more options and directions for using polling tools, and considerations for large classrooms. You can also leverage more informal exercises, such as asking students to identify their “muddiest point,” or the most confusing aspect of the lesson. Or you might have students identify two or three key takeaways from the lesson and write them down on a notecard, which they submit to you (via paper or electronically) as their “exit ticket” for class.

You can also look at course data—assignments, exam scores, writing samples—to gauge where students are performing well versus where they may be struggling with the course material. There have been an abundance of research studies demonstrating the benefits of different pedagogical strategies, which you might consider implementing in your course to facilitate more effective student engagement with the material and retention of critical concepts. Depending on the performance trends you observe, you might also identify opportunities to improve assignments or modify assessments.

Regardless of how you gather data, ground your observations by looking for patterns in student feedback or course data to identify where you can make changes.

Plan

Once you’ve observed the impacts of your current teaching approach, generate a course of action that involves changing something in your practice or course materials. Decide what to change, where, and when.

Remember, you don’t need to change everything all at once—this is an iterative process. Maybe you’ve heard that active learning is effective for engaging students, but you’re used to delivering more conventional lectures. Rather than throwing out all of your presentation slides, find places within a particular lecture where you can build in moments of interaction for students. Or, to give students opportunities to engage with their peers, you might provide a discussion prompt for pair or small group work.

Act

Carry out the change. Remember, if you’re teaching a smaller class, you can assess the impact of your actions during the class by observing how students work together and inviting them directly to give feedback on the changes you’ve made. Alternatively, in a larger class, you may want to poll or survey students on the impact of the change.

Reflect

Notice the effects of your change and plan your next actions accordingly, thus beginning another cycle of action research. Review the teaching goals you set, and ask yourself whether you accomplished what you intended. Consider the next steps to progress achievement of your teaching goals.

Make Reflective Teaching a Habit

It’s easy to get overwhelmed during the academic year, which can sometimes cause us to go on autopilot and lose track of why we do things. Making reflective teaching a habitual part of your teaching process can help you remember to check in with yourself. Habitual reflection helps you decide when and where to make iterative and intentional changes to instruction.

Maintain a Teaching Journal

While you might write reflective notes in the margins of your lesson plan or the speaker notes of your slides, it may be difficult to remember to refer to these artifacts if your notes are scattered in different documents and presentations. Journal-writing is an effective tool for educators to engage in structured self-reflection (Hiemstra, 2001). After each class, consider taking a moment to write in a dedicated teaching journal and respond to the following prompts (Brookfield, 2017):

- What went well?

- What challenges did I encounter?

- How did I or should I address those challenges?

Document Course Design Changes

How have you revised your course since the first time you taught it? To keep track of different iterations of your teaching artifacts (syllabi, lecture slides, assignment sheets, etc.), have a dedicated Google or Box folder where you upload these materials each time you teach the class, with subfolders organized by year/quarter. You can refer to these materials when preparing for performance or promotion reviews, as evidence of your progress in achieving your teaching goals and efforts to improve the learning experience for your students.

Engage in Critical Reflection

Critical reflection calls for instructors to actively cultivate an awareness of their positionality and the ways that their intersecting social identities impact their teaching work (Kishimoto, 2018; Tatum, 2003; Hurtado, 1996). Developing your capacity for critical self-reflection can help you recognize implicit bias and rethink your assumptions about education and society, encouraging you to adopt more inclusive teaching practices (Liu, 2015).

To set teaching goals informed by critical reflection, consider the assumptions and hierarchies that inform your discipline and how your current teaching practices or the content of your curriculum align. Are there new or different perspectives that could be included from your field? If you’re teaching a foundational course for the discipline, is there context that you can provide students about the axes of power that often determine what gets taught or the kind of research that is rewarded? Alternatively, you might reflect on the role you occupy as an authority figure in the classroom, and the ways that you embody and enact that authority with students. Consider ways to cultivate student belonging, which benefits all student learners. For strategies to cultivate a welcoming and inclusive classroom, see Preparing to Teach: Fostering and Sustaining Student Belonging Throughout the Term.

Citing this Guide

UCLA Teaching and Learning Center (TLC). (2025). Leveraging Self-Reflection to Improve Your Teaching. Teaching and Learning Center at the University of California, Los Angeles. Retrieved [today’s date].

Additional Resources

CEILS Teaching Guide: Self Assessment

CEILS Teaching Guide: Other Forms of Evaluation

UC Davis Center for Educational Effectiveness Reflection and Metacognition Series: Part 1: Reflecting on Teaching Practice.

References

Asad Juma, A. (2024). Self-reflection in teaching: A comprehensive guide to empowering educators and enhancing student learning. International Journal of Science and Research Archive, 12(1), 2835–2844. https://doi.org/10.30574/ijsra.2024.12.1.1113

Brookfield, S. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher (Second edition). Jossey-Bass.

Dewey J. (1933). How we think. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books. (Original work published 1910).

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Fullan, M. (1991). The new meaning of educational change. New York: Teachers College Press.

Hurtado, A. 1996. The Color of Privilege: Three Blasphemies on Race and Feminism. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Jakfar, A. E., & Rahmatillah, R. (2023). A systematic review on the significance of reflective teaching in teaching performance. EnJourMe (English Journal of Merdeka) : Culture, Language, and Teaching of English, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.26905/enjourme.v8i2.11785

Kishimoto, K. (2018). Anti-racist pedagogy: from faculty’s self-reflection to organizing within and beyond the classroom. Race Ethnicity and Education, 21(4), 540–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2016.1248824

Kirpalani, N. (2017). Developing Self-Reflective Practices to Improve Teaching Effectiveness. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 17(8). Retrieved from https://www.articlegateway.com/index.php/JHETP/article/view/1436.

Liu, K. (2015). Critical reflection as a framework for transformative learning in teacher education. Educational Review, 67(2), 135–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2013.839546

Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting & task performance. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Louis, K.S. and Kruse, S.D. (1996). Professionalism and community: Perspectives on reforming urban schools. Newbury Park, CA: Corwin.

Lubbe, W., & Botha, C. S. (2020). The dimensions of reflective practice: a teacher educator’s and nurse educator’s perspective. Reflective Practice, 21(3), 287–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2020.1738369

Lysaker, M. Y. (2021). Building Equity in the String Classroom Through Reflective Practice: Questions for Self-Reflection. American String Teacher, 71(1), 57–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003131320975875

Moon, J. A. (1999). Reflection in learning and professional development: Theory and practice. Routledge.

Norton, L. (2019). Action research in teaching and learning: a practical guide to conducting pedagogical research in universities (Second edition). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

O’Neill, J., & Conzemius, A. (2006). The power of SMART goals: using goals to improve student learning. Solution Tree.

Pedrosa-de-Jesus, H., Guerra, C., & Watts, M. (2017). University teachers’ self-reflection on their academic growth. Professional Development in Education, 43(3), 454–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2016.1194877

Sutton, R. E., & Wheatley, K. F. (2003). Teachers’ Emotions and Teaching: A Review of the Literature and Directions for Future Research. Educational Psychology Review, 15(4), 327–358. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026131715856

Tatum, Beverly Daniel. (2003). Why are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? And Other Conversations About Race. New York: Basic Books.