Getting Started with Digital Accessibility in Teaching and Learning

April 2025

What?

Digital accessibility is the practice of designing and creating digital content so that all people can engage with and use the materials, regardless of their disability or need for assistive technology. In the context of instruction, digital accessibility considerations impact the design and delivery of course material as well as the structure of learning activities involving educational technology.

Including digital accessibility features in course design supports every student’s learning and is a key component of UCLA and UC commitments to inclusive excellence. Goal 4 of UCLA’s Strategic Plan prioritizes access, opportunity, and equity in realizing an institutional culture of inclusive excellence and specifically aims to increase the number of courses that are (re)designed in ways evidenced to improve learning and support all students in achieving their educational goals.

Research underscores the profound impact of accessibility and accommodations on student success (Burgstahler, 2015). Increasing accessibility improves learning outcomes, retention, and time to degree for students with disabilities (Murray et al., 2014; Belch, 2004). Many teaching strategies that support students with disabilities also improve learning outcomes generally. For example, digital accessibility allows all students to access course material in multiple modalities, as well as enabling them to pause and review content. By cultivating an inclusive learning environment, we help every student reach their full academic potential. See the TLC Inclusive Teaching Guide.

There are numerous examples of course material that need to be made digitally accessible and then provided to students via an equally effective accommodation plan aligned with their disability needs. For instance, recorded lectures and instructions should have captions. Documents such as worksheets or reading assignments should include alt-text images, a header structure, proper reading order, and descriptive URL links. If shared with students in PDF format, the documents must be decipherable to a screen reader and not just presented as a scanned image. When creating course materials in Bruin Learn, pages (including quizzes and surveys) should have header structure, descriptive URL links, and alt-text for images just like a document you might upload to BruinLearn. Running the embedded accessibility checker (Ally) can help identify where there may be issues with pages. Finally, many instructors use educational technology and other digital tools, including eBooks, that are external to the Bruin Learn environment. These also must be evaluated for digital accessibility, a process that typically happens during the procurement process within the university purchasing office when Learning Tools Interoperability (LTI) integration enables access to these educational technology tools via Bruin Learn. Freeware, including mobile applications, should also be vetted for accessibility.

Why?

The U.S. Department of Justice (DoJ) has mandated that state and local government institutions, including UCLA, meet WCAG 2.1 standards by April 24, 2026, to ensure compliance with accessibility laws and regulations (see final rule). This deadline underscores an urgent need for the university to reaffirm its commitment to inclusive excellence, support the success of all students, and take immediate action to eliminate barriers that prevent individuals with disabilities from equally and fully participating in academic and campus life.

What is WCAG 2.1?

WCAG 2.1, level AA refers to Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, a set of technical standards that make websites more accessible to people with disabilities. In terms of teaching and learning, applying these principles means that all students can easily access and interact with course materials, documents, web pages, and other course media. These regulations, consistent with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), represent a significant step forward in ensuring digital accessibility for people with disabilities. By requiring compliance with WCAG 2.1 level AA, mandating alternative text for images, and improving navigability and usability, these updates aim to create a more inclusive digital environment (Web Accessibility Initiative).

Making course content accessible should not be viewed as a one-time effort to achieve compliance. Instead, the commitment by instructors to do so serves an urgent yet ongoing instructional need and thus represents a new and permanent aspect of UCLA’s teaching and learning ecosystem.

It is helpful to understand the range of disabilities your students may be navigating, as each has different digital accessibility needs. A few examples include:

Limited Mobility

Students may be experiencing a temporary or permanent physical disability that inhibits their motor skills. Assistive devices support web and document navigation for individuals with limited mobility.

Blind and low vision

Blind and low vision individuals may use a screen reader or screen magnifier to navigate documents and web pages. These tools read the code embedded in digital materials to navigate through these materials, such as navigating through the various sections of an article or website.

Colorblind

Everyone benefits from using color contrast design, but in particular, color-blind individuals or individuals with low vision need appropriate color usage in text and images to be able to read/view them.

Deaf and hard-of-hearing

Deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals rely on captions on videos and transcripts of audio recordings. These benefit hearing individuals in loud spaces as well.

How?

Instructors play a critical role in ensuring all students can access and use digital course materials and educational technology to support learning activities in a class. We appreciate that every new instructor and teaching assistant will likely require assistance as they begin their instructional roles, ensuring that digital accessibility becomes an integral and ongoing part of their inclusive teaching practices. We also anticipate that many experienced instructors will need support to strengthen their existing course materials to meet digital accessibility requirements. The Teaching and Learning Center (TLC), Disabilities and Computing Program (DCP), and Bruin Learn Center of Excellence (CoE) are committed to helping instructors achieve WCAG 2.1, level AA standards with respect to all course materials and learning tools. We next provide several strategies instructors may adopt to incorporate digital accessibility into course design.Getting Started

Please note that UCLA main campus and UCLA Extension each use a different custom version of the learning management system Canvas. Extension’s version keeps the original name Canvas, and the main campus uses the name Bruin Learn. For the purposes of the guide they are interchangeable.Use Captions

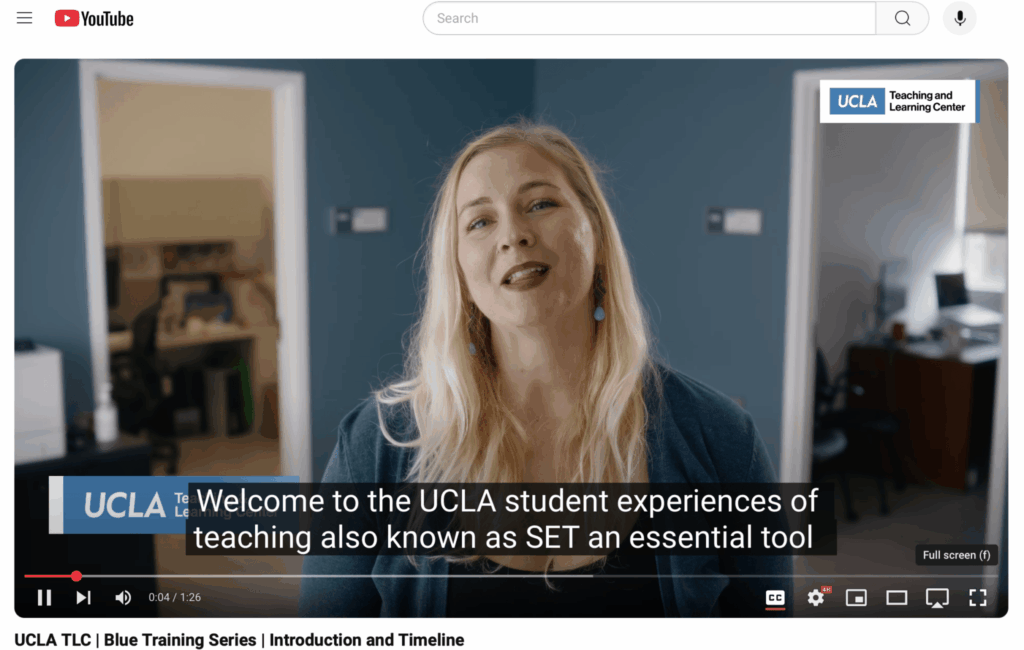

For any videos used in course materials or to deliver course content or information for students, ensuring they have captions is the best way to make the content accessible. At UCLA, captions are automatically enabled in Kaltura, the video streaming and hosting service integrated into Bruin Learn. Kaltura is the recommended tool for storing and sharing media, offering automatically generated captions, enhancing accessibility for all users. For more information about Kaltura, visit the CoE Kaltura page.At UCLA Extension, captions are automatically enabled in Panopto. For more information about Panopto, visit the Panopto article on Extension’s Instructor Knowledge Base.If you are using Kaltura or Panopto to deliver your videos, there is nothing you need to do to make the captions available to students, as they are automatically turned on. However, while the autogenerated captions are mostly accurate, it is likely that you will have to review them to make sure things like names or scientific terms are spelled correctly. For more information on how to edit captions on Kaltura, please visit this article in the Kaltura Knowledge Center, and for more information on Panopto, please visit this article in Extension’s Instructor Knowledge Base.If, however, you choose to share or include YouTube videos or other videos uploaded from the internet or recorded at home and not delivered via Kaltura or Panopto, remember to turn on captions. The screenshots below show a video with the captions off and with the captions on. The “CC” button on the bottom right of the screen is highlighted in yellow in the second image, and is what you would use to make captions visible or turn them on or off.

Use Header Structure in Documents and Bruin Learn Pages

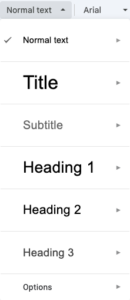

To facilitate proper reading order of text on web pages and documents (e.g., syllabus, worksheets, slide decks, Bruin Learn pages, etc.), organize the content using a logical hierarchical structure to signal different sections and subsections (e.g., heading 1, heading 2). Document structure is important for adaptive technology users who rely on it to move through the text and understand the information. Without these signposts, a screen reader simply scans a page or document as one long section of text without sections and emphasis of particular details.

Header structure is available in all digital writing platforms (e.g., Google Docs, Word, Bruin Learn). Individual tutorials are provided for each platform, but they follow a similar format shown in the accompanying figure below. The author chooses to apply a heading 1, heading 2, and so on to any words on the page, including “normal text” for body paragraphs. Simply highlight a section of text and apply the desired header format. You may modify the format for each header type itself, including the font type, size, color, and line spacing.

Note that while some applications include “Title” and “subtitle” as options, we recommend using Heading 1 for the title and avoiding using “Title” or “Subtitle”. The reason for this is that when documents are saved as PDFs or other external formats these identifiers are not recognized.

Below is a screenshot of the header structure available in Google Docs:

Tutorials for using header structure in documents and pages

How to use Headers in BruinLearn

How to use Headers in Google Docs

Create Accessible slide Decks and Powerpoint Presentations

Create accessible slide decks by keeping the following guidelines in mind:

- Use PPT or Google templates so that when you export to PDF this will preserve the structure for screen readers. If you do this, you cannot add text boxes or titles; you must use the format from the template.

- Add alt-text to all images.

- Use large, sans-serif fonts (e.g., Arial, Verdana) for readability. A 24 pt font is considered ideal, but you can also try a “back of the room” readability test to see what works for your audience.

- Ensure high color contrast between the text and background. Try this color contrast checker if you are unsure.

- Limit text and bullet points on each slide to increase readability.

- Use simple layouts; avoid overloading slides with images or complicated designs.

Create Accessible PDFs

You can create accessible PDFs from accessible Word documents or accessible Google Docs. Starting with an accessible document is important. If you follow best practices in either Word or Google Docs, and then use save or export to PDF (not print to PDF, unless you are printing). Exporting from accessible Word to PDF will save more of the accessibility features, such as heading structure and alt-text, than Google Docs. Therefore, it is recommended to save your Google Doc as a DOCX file and then export from MS Word to PDF.

UCLA provides licenses for Adobe Acrobat (along with other Adobe products) to employees. You will need to install Adobe Acrobat to take full advantage of its many features, including tools that support accessibility.

Run the PDF Checker once it’s in Adobe Acrobat:

- Open the PDF in Adobe Acrobat and run an Accessibility Check (Tools > Accessibility > Full Check).

- Use the guidance provided to address each issue and run the accessibility checker again.

- Continue until the document passes the accessibility check.

If you are using files that you did not create yourself, such as PDFs of articles, you must also ensure that these documents are accessible. Use Adobe’s Accessibility Check to scan all PDFs in your course and make updates as needed. Instructors can contact bruinlearn-support@it.ucla.edu for assistance. Adobe also provides a recorded webinar on PDF remediation that can also support your skill development. Also see Adobe instructions on accessible PDFs.

Moving PowerPoints and Google Slides to PDF

The only way to make PPTs and Google Slides fully accessible is to use their built-in slide layouts (found in Home>layout in PPT and Slide>apply layout in Google Slides). Using the built-in template will retain the slide title, body text, and images in an accessible format.

The DCP at UCLA offers step-by-step guidance on creating accessible PDFs in its Faculty Quick Guide to Building an Accessible Course.

Use Accessible Tables and Spreadsheets

To create accessible tables, first name your table. Microsoft Excel automatically gives tables generic names (table 1, table 2). Providing descriptive names will help everyone be able to find the correct table. Second, use table headers. Similar to the header structure discussed in documents, tables also need headers:

- Place the cursor anywhere in a table.

- On the Table Design tab, in the Table Style Options group, select the Header Row checkbox.

- Type the column headings.

Simple tables with tabular data are the most accessible. Avoid using tables for layout or other non-data functions.

Tutorials for accessible spreadsheets

Best Practices for Accessible Excel Spreadsheets

Accessibility Practices for Google Sheets

Install accessibility checker for Google Sheets

Use Alternative Text (Alt Text)

Alt text is a description of an image that a screen reader reads to describe the picture. Without alt text, students using screen readers just hear “image.” You should include alt text for any image you display in class or any image you include in a slide deck, documents, or on your course site in Bruin Learn.

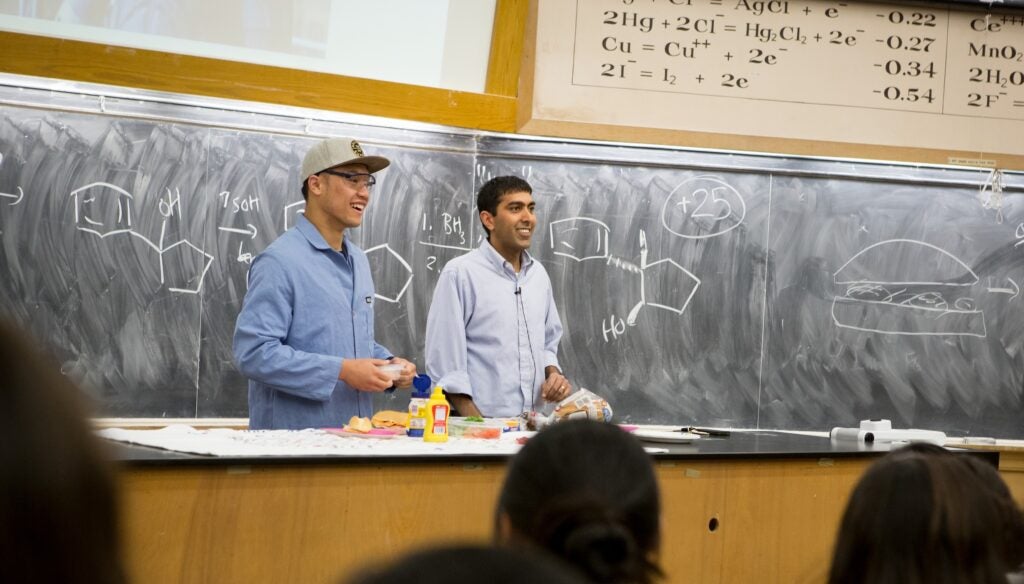

For the following image, an alt text example with an insufficient explanation might be “a science class”. By contrast, an improved description would be “Two male instructors stand in front of a class with hamburger ingredients on a desk in front of them and a diagram of a molecule and a hamburger on a blackboard behind them.”

To write alt text, adhere to the following guidelines:

- Be as specific as possible in describing the image.

- Keep the description brief (100 characters maximum).

- Include a keyword or phrase in the description.

- Avoid starting the description with “Image of …” or “Picture of …” and simply describe the image.

- If there is any text that is part of the image, state the text information in the description. This recommendation applies to logos, which, when described using alt text should include the full name of the organization to which the logo refers.

Use Descriptive Links

It is common practice to include website URLs in email messages, documents, and slides that direct students to additional resources to support their learning. Avoid copying and /pasting the full URL text; instead, create a descriptive text link and embed the URL in the text. Moreover, use unique and specific language that describes the link destination, rather than vague text such as “click here,”, “link,”, “article,”, or “read more.”. The link text should make sense without the surrounding sentences or content, conveying the function and purpose of the link when read by a screen reader. Below are some examples of link text and ways to improve those descriptive links:

Instead of “ Click here to download our terms and conditions”

Change to: Download our terms and conditions (PDF, 4.2MB)

Instead of “Go to this web page for our master’s course list”

Change to: The Courses for 2019-20 page has a full list of our master’s courses

Instead of “Visit us our web pages: http://www.imperial.ac.uk/openaccess”

Change to: Visit our Open Access site

Follow Zoom Best Practices

Many instructors, even those teaching in-person courses, hold synchronous sessions over Zoom from time to time. These sessions can range from office hours to review sessions to full lectures or a discussion section,; as well as any Zoom sessions for fully online classes. To ensure all students can participate fully, use the guidelines below.

For Everyone

Students may be experiencing a temporary or permanent physical disability that inhibits their motor skills. Assistive devices support web and document navigation for individuals with limited mobility.

For Screenreader Users, Blind, and Low Vision Participants

Vocalize all items on screen

For Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Participants

Live AI or CART Captioning (live person writing captions, provided by the Center for Accessible Education (CAE)

Speak facing the camera, use a mic, and enunciate

Use Available Accessibility Checkers

Use the Ally Tool in BruinLearn

Ally, which is available to both UCLA instructors and students, is an accessibility tool integrated into Bruin Learn that identifies inaccessible course materials. Ally conducts an automatic content assessment to detect issues with files uploaded to Bruin Learn or pages and images on the course site itself. You may have seen the red, yellow, or green indicators next to images or documents in your course sites already. Ally generates an accessibility score and suggests alternative formats such as audio, HTML, ePub, and tagged PDFs to remedy the detected accessibility concern. Ally offers some guidance for improving document accessibility. Instructors can contact bruinlearn-support@it.ucla.edu for assistance to mitigate any digital accessibility issues in Ally.

Resources for Ally and Its Application to Content in Bruin Learn

DCP Guide to the Bruin Learn Ally Tool

Use Accessibility Checkers in BruinLearn, Google Docs, Microsoft, and Adobe

Most word processing programs also have accessibility features and checkers built into them. When creating digital materials for your courses, you can use these to check the accessibility of your documents. In addition to Ally, Bruin Learn also has a built-in accessibility checker that covers content on all pages, as does Adobe Acrobat.

Additional accessibility checkers:

Bruin Learn Accessibility Checker

Microsoft Word Accessibility Assistant

Accessibility Features in Google

Adobe PDF Accessibility Checker

Accessibility and Artificial Intelligence (GenAI)

Over the past year, there have been and continue to be advancements in GenAI as the field is rapidly evolving and expanding. Some examples of GenAI tools are OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Microsoft’s Copilot and Google’s Gemini. UCLA faculty, staff, and students have access to GenAI tools through CoE (see link below). Some newer GenAI tools are focused on accessibility. Many of these new accessibility tools may not yet be reliable or fully available to UCLA. However, using available GenAI tools for alt text creation may be particularly helpful.

UCLA GenAI Tools: View information on how to access Co-Pilot and general guidance on using AI tools.

AI as my Copilot – Improved ALT-text: This blog post provides an example of how AI can be used to more efficiently create alt text for images.

Please see our teaching guide on using generative AI in teaching and learning for more information.

Citing this Guide

UCLA Teaching and Learning Center (TLC). (2025). Getting Started with Digital Accessibility in Teaching and Learning. Teaching and Learning Center at the University of California, Los Angeles. Retrieved [today’s date].

Additional Resources

Center for Accessible Education (CAE)

Disabilities and Computing Program (DCP)

Bruin Learn Center of Excellence (CoE)

TLC Best Practices for Teaching and Learning with Zoom

BruinLearn (Canvas) Accessibility Checker

Distinguishing between Accessibility, Usability, and Inclusion

Information on Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

DCP Video Presentation “What is Accessibility” Covers laws that apply ADA, 508, WCAG, etc, and basic information about accessibility (6 minutes)

References

Belch, H. A. (2004, May). Retention and students with disabilities. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 6(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.2190/MC5A-DHRV-1GHM-N0CD

Bong, K. W. & Chen, W. (2024). Increasing faculty’s competence in digital accessibility for inclusive education: a systematic literature review, International Journal of Inclusive Education Volume 28, Issue 2. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13603116.2021.1937344#abstract

Burgstahler, S. (2015). Impact of Faculty Training in Universal Design of Instruction on the Grades of Students with Disabilities in Universal Design In Higher Education from Principles to Practice. Harvard Education Press, 2nd edition.

Dewsbury, B. & Brame, C. J. (2019). Inclusive teaching. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 18(2), fe2.

Moriña, A. & Carballo, R. (December 2017). The impact of a faculty training program on inclusive education and disability. Evaluation and Program Planning. vol 65 Pages 77-83.

Murray, C., Lombardi, A., Seely, J. R., & Gerdes, H. (2014). Effects of an intensive disability-focused training experience on university faculty self-efficacy. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 27(2), 179–193. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1040537

Murray, C., Lombardi, A., Wren, C. T., & Keys, C. (2009). Associations between prior disability- focused training and disability-related attitudes and perceptions among university faculty. Learning Disability Quarterly, 32, 87-100.

Davies, Patricia L.; Schelly, Catherine L.; Spooner, Craig L. (2013) Measuring the Effectiveness of Universal Design for Learning Intervention in Postsecondary Education. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, v26 n3 p195-220.